Object-Oriented Programming explained simple

Published on Oct 6, 2025

Watch the video version of this article.

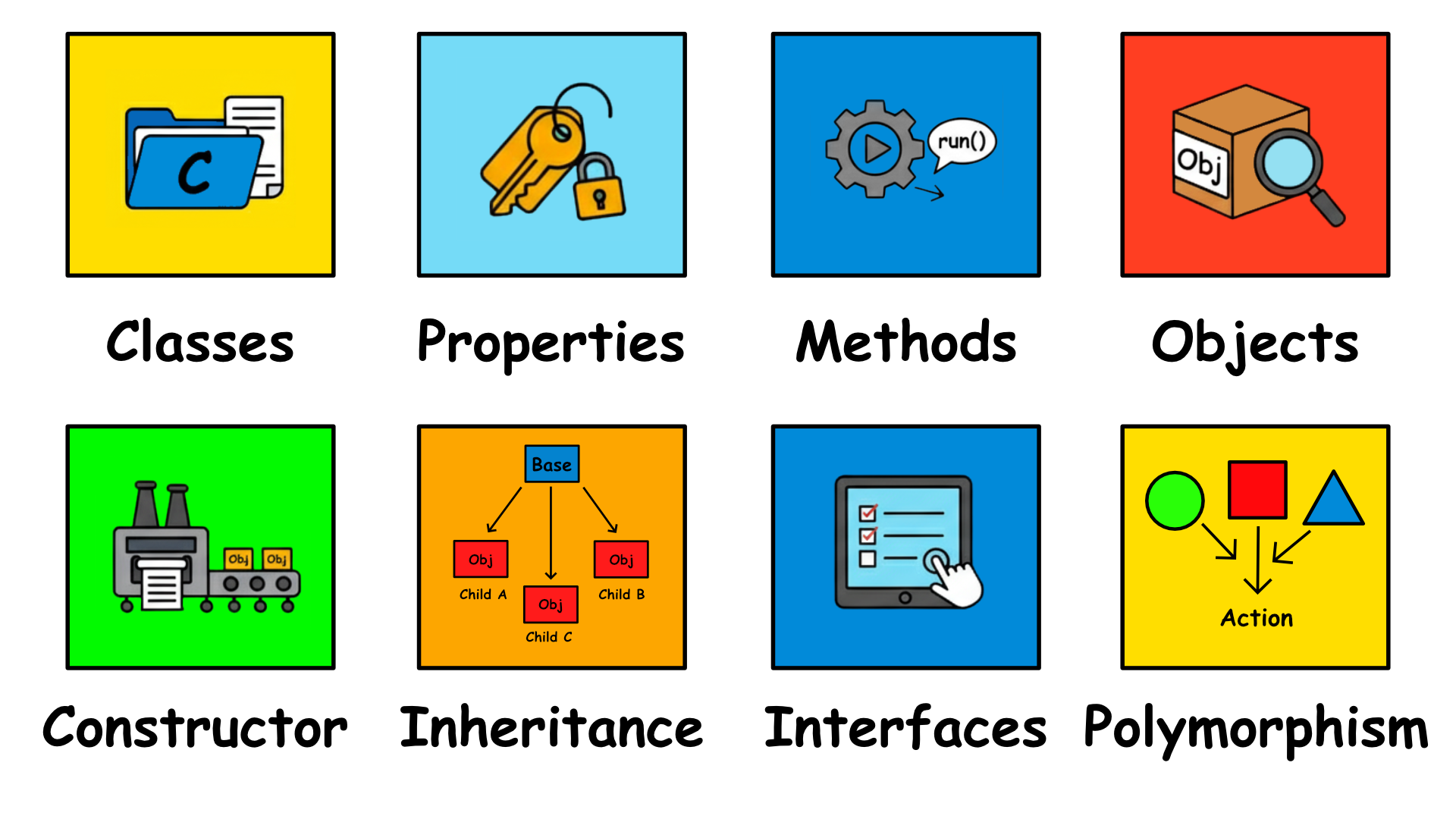

OOP is simply a way to organize your code: instead of having variables and functions scattered everywhere, you group them into “classes” that represent real-world things. A Dog has properties like name and methods like bark().

Now, OOP is great for medium-sized projects, but when it grows too much it can become a maze of classes inheriting from classes that implement interfaces that extend other classes… (yes Java, we’re looking at you 👀). The key is using it in moderation.

Why use OOP?

- Organization: Your code is better structured

- Reusability: You can use the same classes in different places

- Maintenance: It’s easier to find and fix bugs

- Collaboration: Other programmers understand your code more easily

- Scalability: You can add new features without breaking existing code

What is a Class?

A class is like a mold or template for creating similar things. It’s like a house blueprint: it’s not a real house, but it contains the instructions to build many houses.

Imagine you want to program different types of dogs. Without classes, you’d have to do this:

# Without classes - repetitive and disorganized

dog1_name = "Max"

dog1_breed = "Labrador"

dog1_age = 3

dog2_name = "Luna"

dog2_breed = "German Shepherd"

dog2_age = 5

def bark_dog1():

print("Max says: Woof!")

def bark_dog2():

print("Luna says: Woof!")With classes, you can do this:

# With classes - organized and reusable

class Dog {

name

breed

age

function bark() {

print(name + " says: Woof!")

}

}The Dog class is the mold. It contains the characteristics (name, breed, age) and behaviors (bark) that all dogs will have.

Properties and Methods

Classes have two types of elements:

Properties (Variables)

These are the characteristics or data that the object stores:

class Dog {

name # Property

breed # Property

age # Property

energy # Property

}Methods (Functions)

These are the actions that the object can perform:

class Dog {

name

breed

age

energy = 100

function bark() { # Method

print(name + " says: Woof!")

}

function run() { # Method

energy = energy - 10

print(name + " is running!")

}

function sleep() { # Method

energy = 100

print(name + " is sleeping... zzz")

}

}What is an Object?

An object is a “real thing” created using the class as a mold. It’s like building a real house using the blueprint.

# Create objects (instances) of the Dog class

max = new Dog()

max.name = "Max"

max.breed = "Labrador"

max.age = 3

luna = new Dog()

luna.name = "Luna"

luna.breed = "German Shepherd"

luna.age = 5

# Use the objects

max.bark() # "Max says: Woof!"

luna.bark() # "Luna says: Woof!"Now you have two objects (max and luna) created from the same class (Dog), but each one has its own data.

Constructor

The constructor is a special method that runs automatically when you create a new object. It allows you to initialize the properties from the beginning:

class Dog {

name

breed

age

energy

# Constructor - runs when creating the object

constructor(initial_name, initial_breed, initial_age) {

name = initial_name

breed = initial_breed

age = initial_age

energy = 100

}

function bark() {

print(name + " says: Woof!")

}

}

# Now it's easier to create objects

max = new Dog("Max", "Labrador", 3)

luna = new Dog("Luna", "German Shepherd", 5)Inheritance

Inheritance is when one class “inherits” properties and methods from another class. It’s like saying “this new class is like the previous one, but with some differences”.

Imagine you want to create different types of animals:

# Parent class (base class)

class Animal {

name

age

energy

function constructor(initial_name, initial_age) {

name = initial_name

age = initial_age

energy = 100

}

function sleep() {

energy = 100

print(name + " is sleeping...")

}

function eat() {

energy = energy + 20

print(name + " is eating")

}

}

# Child class - inherits from Animal

class Dog extends Animal {

breed

function constructor(initial_name, initial_age, initial_breed) {

super(initial_name, initial_age) # Call parent constructor

breed = initial_breed

}

function bark() { # Method specific to Dog

print(name + " says: Woof!")

}

}

# Another child class

class Cat extends Animal {

color

function constructor(initial_name, initial_age, initial_color) {

super(initial_name, initial_age)

color = initial_color

}

function meow() { # Method specific to Cat

print(name + " says: Meow!")

}

}Now you can create dogs and cats that automatically have the Animal methods:

max = new Dog("Max", 3, "Labrador")

whiskers = new Cat("Whiskers", 2, "Black")

max.sleep() # Inherited from Animal

max.bark() # Specific to Dog

whiskers.eat() # Inherited from Animal

whiskers.meow() # Specific to CatInterfaces

An interface is like a contract that says “any class that uses this interface MUST have these methods”. It doesn’t say how to do it, only what must be done.

# Interface (contract)

interface Flyer {

function fly() # Any class implementing Flyer MUST have this method

function land() # And also this method

}

# Class that implements the interface

class Bird implements Flyer {

name

function constructor(initial_name) {

name = initial_name

}

function fly() { # REQUIRED by the interface

print(name + " is flying!")

}

function land() { # REQUIRED by the interface

print(name + " has landed")

}

function sing() { # Additional method specific to Bird

print(name + " is singing")

}

}

class Airplane implements Flyer {

model

function constructor(initial_model) {

model = initial_model

}

function fly() { # REQUIRED by the interface

print("Airplane " + model + " is flying")

}

function land() { # REQUIRED by the interface

print("Airplane " + model + " has landed")

}

}Interfaces ensure that different classes have compatible methods, even though they work differently inside.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism sounds complicated, but it’s super simple: it means that different objects can respond to the same method in different ways. It’s like saying “speak” to a human and to a dog - both understand the instruction, but each one executes it differently.

Imagine you have different animals and you want them all to “make sound”:

class Animal {

name

function constructor(initial_name) {

name = initial_name

}

function make_sound() {

print(name + " makes some sound")

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

function make_sound() { # Overrides the parent method

print(name + " says: Woof!")

}

}

class Cat extends Animal {

function make_sound() { # Overrides the parent method

print(name + " says: Meow!")

}

}

class Cow extends Animal {

function make_sound() { # Overrides the parent method

print(name + " says: Moo!")

}

}Now you can use polymorphism:

# Create different animals

animals = [

new Dog("Max"),

new Cat("Whiskers"),

new Cow("Lola")

]

# Polymorphism in action

for animal in animals {

animal.make_sound() # Each animal responds differently to the same method

}

# Result:

# Max says: Woof!

# Whiskers says: Meow!

# Lola says: Moo!The great thing about polymorphism is that you can treat different objects the same way, regardless of their specific type. Your code doesn’t need to know if it’s a dog or a cat - it just tells them “make sound” and each one knows what to do.

Conclusion

Object-Oriented Programming is not a mystical and complicated concept. It’s simply a way to organize your code using concepts you already understand from real life.

Think of it this way:

- Variables → become properties of objects

- Functions → become methods of objects

- Organization → is done with classes

- Reusability → is achieved with inheritance

- Consistency → is guaranteed with interfaces

You no longer need to have 50 loose variables and 30 scattered functions. With OOP, you organize everything into logical classes that represent real-world things.